Connections in Yellow

This newsletter has English and Spanish versions. To choose which language you receive, visit your settings on Substack, find this newsletter under Subscriptions, and select the language(s) you want.

Leer en español aquí.

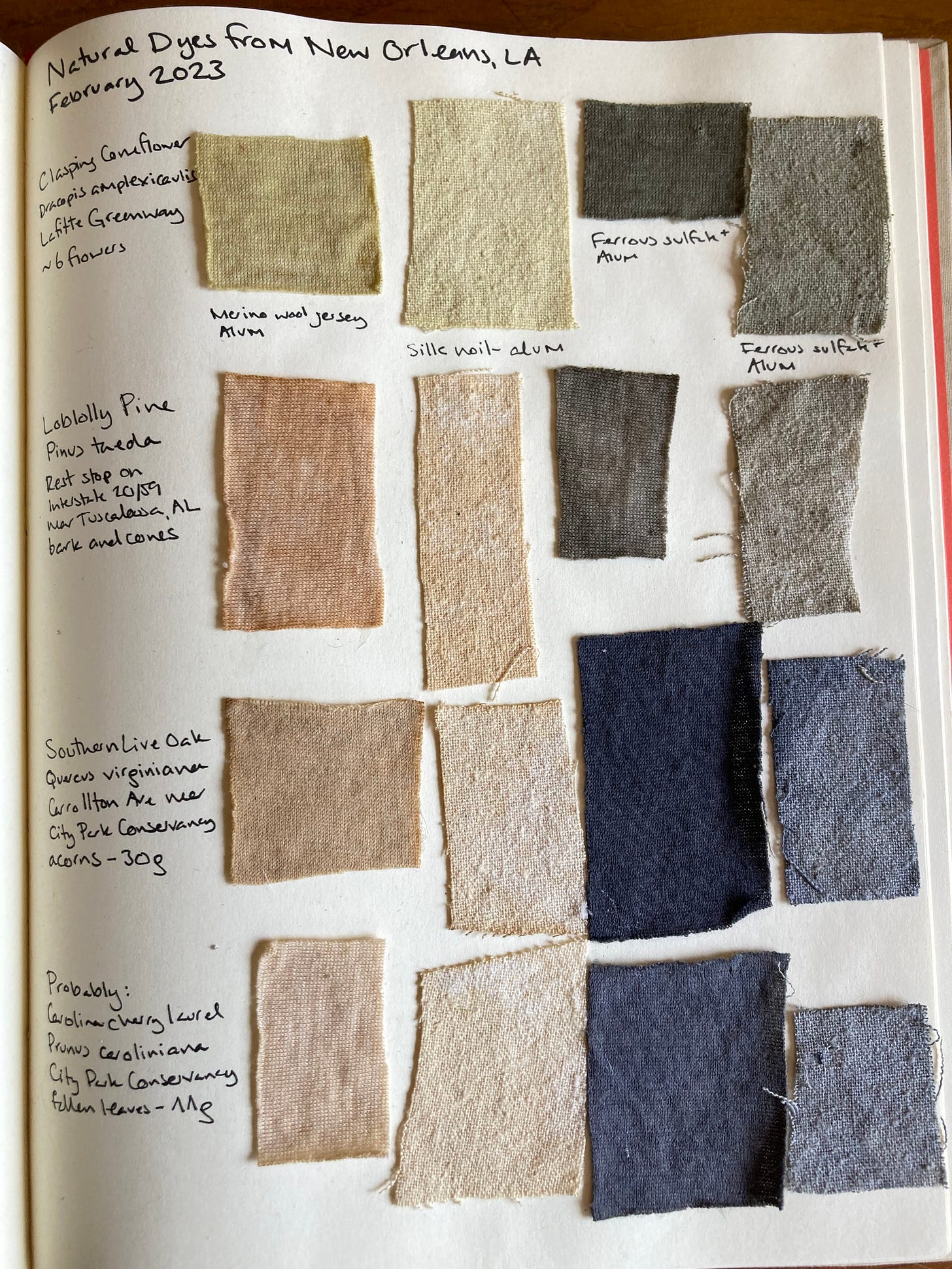

A couple years ago I took an online course with natural dye maestro Raul Pontón: Tintorería mexicana. These lessons were fundamentally place-based, using Mexican sources of natural color: cochineal for Mexican red, indigo for Mexican blue, logwood for Mexican purple, Brazil wood for Mexican pink; and using local dye recipes, ingredients and that would be easily accessible in Mexico and processes that would integrate easily into a Mexican way of life. Many of these recipes were impossible for me to replicate in my Chilean apartment: ingredients like wood ash aren’t easy for me to come by, and I don’t have the space to let an indigo vat ferment for weeks. But learning about these methods helped me understand how color traditions result from a place, a culture, a way of life. I can learn from tintorería mexicana but I can’t really do it without going to Mexico. Whether I’m in Viña del Mar or Ohio, I have to find my own ways.

Indigo, cochineal and logwood are Mexican ingredients that have long histories internationally thanks to colonialism, and are a staple of many dyers’ practices today. I use all of these ingredients, usually imported (with the sometimes exception of indigo). There just aren’t that many natural dyes that give colorfast red, blue or purple. But yellow is a different story. The yellows of tintorería mexicana such as pericón and cuscuta are not available to me, but no matter: yellow is everywhere. The most common dye color in nature, wherever you are you most likely have access to several sources of yellow. From lemon to sunshine to golden to earthy, from strong and colorfast to pale and fleeting, put a plant in water, add a little heat, and there’s a good chance you’ll get some yellow.

This can make yellow feel not special, but I like knowing that wherever in the world I go, I’ll find that place’s unique yellow.

Some yellows, like oxalis and pomegranate, are colorfast enough and abundant enough where I live to become staples in my practice, while others are more for experiments in local color, records of plants I’ve visited, color memories.

Oxalis and pomegranate are the most used yellows for my dye practice in Chile, while homegrown weld and foraged goldenrod are my Ohio favorites, although I use many sources of yellow in my practice depending on the season and the shade I’m hoping to achieve. Onion skins are a staple that I can count on anywhere I go.

I’ll finish this color appreciation with a song as I always do. I try not to use the most obvious pick for my color songs (not songs that have the color in the title), so this is a piece that I associate with yellow because of its brightness and its key, E major, which I think of as a yellow key.

News

After promising to make time for dyeing while I care for a baby and work and try to do some cooking and cleaning, I did basically no dyeing at all in the past month. No matter, I had a great time being with my baby through some fun milestones like crawling and starting solid food. In the past few days I’ve finally gone back to work on the latest batch of silk scarves and am excited to develop their colors slowly. This newsletter is the best way to keep up with the snail’s pace of new development, and I’ll also post them on Instagram when I’m ready.